(Guiyang,

Guizhou 1986) The most effective way to make friends was, without a shadow of a doubt, by eating out. The choice was modest—either the students’ cafeteria or the

snackbar alley! My routine was to spend dinners with students in the cafeteria.

Everyone toted a metal bowl and utensils. The mess hall was an enormous airline-hanger-like structure, inside of which every kind of food imaginable was displayed in rectangular tin pans that were spread out on twenty to thirty tables. The cost per portion averaged from twenty to thirty cents.

Students squatted on the wall outside the hall and tossed out unwanted surprises (i.e., worms, stones, chips of coal, rancid meat, and UFO’s—‘unidentified fried objects’). These were all flung to the goldfish in the pond or to the local yokels who hung out at meal times: piggies, chickens, cats, dogs, and a friendly flock of fifty or so geese.

I relished the gusto of the local dives in

Guizhou known in Chinese as

xiăochī[1], where I oft times grabbed a quick breakfast or lunch. The scenario was enough to whet any hungry man’s appetite: chickens strutting on tables, dogs gobbling scraps beneath them, white cubes of pork fat sizzling to a crisp, hot peppers strung from the ceiling....

Daily delicacies were served in chipped, cracked bowls, which were “prudently” boiled after every use. I always procured my own metal bowl and wooden chopsticks, since hygiene was not one of the main ingredients.

Following a massive outbreak of

gānyán[2] in Shanghai earlier that year, hepatitis became a rampant epidemic in our region, and after one visit to a student who lay sick in the contagious disease ward of the hospital, I thought it best to take extra precautions!

Raw vegetables spelled suicide. Garden salads, Caesar salads, and soup and salads were not only out of the question, they were unknown—and suicidal. Since it was expedient to boil drinking water for a minimum of twenty minutes, any makeshift bottled drinks or fresh beverages had to be foregone. Understandably, overcautious measures were the best policy.

The regional speciality was

mamma’s five-cent bowl of noodle soup, which made a light lunch or midday snack. (Just hold the pork fat!) For the heartier eater, there was always an

entrée of

jiăozi[3] for twenty- five cents a serving. The average hash-house menu in our province posed no restrictions.

With the exclusion of the stools that I sat on and the Boeing I flew in on, practically anything and everything with legs or wings could be ordered, from fricasseed feline to jellyfish julienne. Deep-fried sticks of dough and a steaming glass of sweetened soy milk provided me with a palatable breakfast, especially in the raw of winter. It was not common practice for restaurants to post a menu, let alone the ingredients of their gastronomic creations.

One morning after class, instead of a routine underground sweet radish for breakfast, I stopped for a bowl of noodle soup at one of the

xiaochi alleys alongside the students’ dorms. Nothing exceptionally peculiar alarmed my palate, so I paid a second visit a week later. As I slurped up the noodles using my chopsticks as a shovel, the short order cook leaned over the counter. The waitress stared at me with a smile.

“How ‘bout that!” she commented. “Foreigners like

gŏuròu!”

[4] “Oh, I’

ve never had the chance to savor dog,” I asserted in the height of presumption.

“Ha!” the two

culinarians let the cat out of the bag. “Last week you wolfed down a bowl and you just lapped up another one now!”

Oh, how I felt like howling! I was too squeamish. Then, the flashbacks—memories of my childhood puppy. I grew queasier. Mental pictures of the wolf-like canines scavenging the streets raced through my mind. White with nausea, I excused myself, thinking, Time to vamoose before I—

Contrary to my initial nauseous reaction and with the exception of an occasional tooth, dog stew steeping with mint and hot chili peppers in a Mongolian hot pot turned into one of my favorite treats. I habitually ordered it for Christmas dinners. Well, until it lost its smack, that is.

Racing down a flight of stairs to the student canteen for breakfast one morn, I had a run-in with a dog that, once upon a time, roamed the campus. The bus driver and a cafeteria worker had savagely lassoed the innocent pup and hanged it in a noose from a wall. Clubbing it repeatedly to a cruel, slow death— To put it bluntly, being an eyewitness of this act of carnage laid my appetite for dog dinners to rest!

Sooner than later, the initial excitement of a foreign cuisine—a nibble of a

băozi[5] here, a nosh of

tángyuán[6] there—soon waned stale. A few weeks after my arrival, my body openly rebelled to the monotony of the region’s repertoire: rice for breakfast, rice for lunch, rice for dinner, and rice for dessert! Day in and day out, my mouth watered in vain for familiar tastes—

lasagne, pizza,

spaghetti alle vongole,

gelati,

biscotti,

un panino, bread...anything! The easiest recipe to duplicate was rice pudding. Give me a break!

In a desperate scurry to satisfy these cravings, I concocted everything from A to

izzard, or should I say gizzard?! I slapped together an improvisation of spaghetti with Chinese noodles and

sautéed tomatoes. I churned out homemade ice cream by boiling and freezing a compound of water, powdered milk, sugar, and eggs. The other

foreignors on the team concocted a mock oatmeal “fantasy” from soggy overcooked rice

[7]—the evening leftovers that were recycled into students’ breakfast, which they seasoned with cinnamon,

raisins, and honey to bamboozle the senses.

One of the major drawbacks in reproducing a non-artificial recipe from back home, which could be discernible to the taste buds, was the absence of recognizable oil. Even when

wokked into Chinese dishes, the local brand required some time for acclimatization.

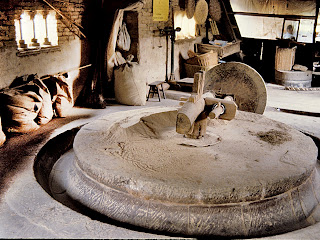

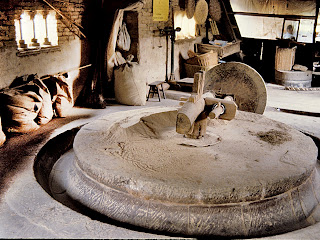

Càiyóu[8] was the variety’s name—a thick nut-brown fluid extracted from

rabe seeds that had to be refined. The refining process caused pitch-black fume to be emitted.

The Chinese poured the desired amount of this crude oil into a preheated wok before cooking. Once the impure vapors dissipated, the other ingredients could be tossed in and fried. Trying to cut corners one day, we nearly burned the house down while refining a pot of this

caiyou, which self-ignited on the balcony and burned for twenty minutes under lid and cover. (Thank heavens we did not have an oil spill!) Thereafter,

we refined spoonfuls at a time just before cooking.

Refined or not, this

unrecog-

nizable condiment definitely did not make an appetizing substitute in dishes that called for olive oil or butter! Potato chips and French fries were edible, but a little hard on digestion. Deserts were undermined in every respect. Pound cakes came out weighing a ton! Oatmeal cookies made with horse-feed oats and this oleaginous substance

didn’t quite hit the spot, but they did have the kick of a horseshoed-hoof.

Early on in the first semester, I was moved to tears when I stumbled upon

pre-sweetened instant coffee in the newly constructed department store. What a change of pace from the cup of boiling hot water and lotus root powder, which tasted like sweetened cornstarch! I had a treat in our third semester when a fellow Chinese teacher showed up at the door with a pack of roasted coffee that he had picked up on vacation, on

Hainan Island.

I brewed the coffee in a pot and strained it with a pair of someone’s unused

panty hose. After discovering that the colors ran, I deemed it best to resort to Turkish-style coffee—grains ‘n’ all. What a relief to find instant coffee towards the end of our stay! Oh how I missed my morning

caffé latte made with freshly ground espresso beans!

It did not take much to please me when new products that resembled back-home favorites hit the shelves. Our team tracked down everything that that matched their taste buds: mock peanut butter—a type of thick gooey caramel sauce, something that would be used to top a sundae—and artificial cola made from chrysanthemum flowers.

My weakness was chocolate, which I found—bars waxy in texture but capable of duping the keenest of taste buds. Whenever we stumbled on something novel, we stocked up for the year!

[1] ‘Snack bars’ pronounced shall chur.

[2] ‘Hepatitis’.

[3] Pork-filled ‘dumplings’ dipped into a bowl of soy sauce, chopped ginger root and spring onions, minced garlic, and dry, crushed chili pepper.

[4] Literally ‘dog meat’, pronounced go row as in “go row your boat.”

[5] Steamed buns filled with pork, chunks of fat, and a sweet bean sauce.

[6] Round sticky-rice dumplings filled with crushed peanuts, coarse grain sugar, and bean paste, served hot in its boiled water.

[7] Called ‘muddy rice’—xī fàn, pronounced she fan.

[8] Literally ‘vegetable oil’, pronounced tsigh yo.Photos various restaurants Copyright Men's Fashion by Francesco.

I had been living and working in China for 4 years, but my interest in the Soviet Bloc had sparked long before when I began studying Russian as an adolescent. It was fanned into flame through Russian friends in high school, after which I majored in Soviet area studies, Russian language and literature, and South Slavic languages at university.

I had been living and working in China for 4 years, but my interest in the Soviet Bloc had sparked long before when I began studying Russian as an adolescent. It was fanned into flame through Russian friends in high school, after which I majored in Soviet area studies, Russian language and literature, and South Slavic languages at university.